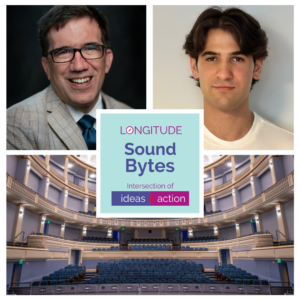

Longitude Sound Bytes

Ep 122: Acoustics in Architecture (Listen)

Ali Kazmaz

Welcome to Longitude Sound Bytes, where we bring innovative insights from around the world directly to you.

Hi, I am Ali Kazmaz, Longitude fellow from Rice University Architecture.

We are exploring the approaches of individuals to contemplation, experimentation, and communication in scientific and creative fields.

For this episode, I had an opportunity to speak with Scott Pfeiffer. Scott Pfeiffer is an acoustics architect. He is one of the nation’s leading figures in acoustics. He was an acoustic consultant and collaborated with the architect in the design of the theater and orchestra pit of the Brockman Hall for Opera.

Join me as I engage in conversation about what acoustics work entails in architecture and the unique journey Scott took in this field. Enjoy listening!

[music]

Ali

How much of a process are you consulting on? This has to be this way, or are you trying to minimize that so that the architect and the client has more freedom?

Scott Pfeiffer

I think I would answer by saying two things. One is all of this, all of the risk taking, and the creation of a new idea and the following of the client’s ultimate desire for the outcome requires an enormous series of collaboration, an overused word, but we have a series of things to solve for us. The structural engineer has some work to do, the mechanical engineering, you know, and we all have a budget, and the architect has work to do. So, under the best of circumstances, we identify ways that we can take those risks together, that, that a new structural idea could enable a new acoustic idea that could enable the outcome to be more successful.

So, our goal is to is not to prescribe what must be, but instead to inform the team as best we can with all the tools. Not leading with a stick to say, don’t do that, but to say, here’s what we’re trying to accomplish. In order to accomplish that we need a surface in here, you know, wherever this is, and we need that to be massive, and we need it to be shaped in a certain way, or within a range of texture that is available to you. And if we do that, really well, we may get to the point that the architect says, But you know, to solve exiting, I need this other thing. So, we have to push and pull a little bit and that’s fine. And the structural engineer says, Well, I can, you know, I can help you with that. Because, you know, I don’t need very thick structure here, I need it up there, or whatever those series of options are. And if we do our job well, we give over the understanding of what we’re trying to accomplish, not the thing that we want, but the why of what we want, so that they can use that to come back to us with an idea that we would not have thought of on our own. And that is that’s where this work is super exciting, that we’re creating something that none of us would have created by ourselves.

Ali

What’s the variety of clients and types of projects you work with, and then do you do any studies on the effects on people?

Scott

We work on quite a wide variety of projects, although the bulk of our work is in cultural buildings. They hire us for the auditorium, but we take that opportunity to make sure that they’re thinking about the acoustics of all the spaces that are under the roof, or, or even those that are outside, so that we’re around having an impact. With each new relationship with each new architectural relationship or design team, we look for the opportunities to visit with them outside of the progress of the project and talk with them about thinking about sound as an influence and all of their design, whether or not we’re on the project or not. We do some research and development work in our office but mostly we’re staying in touch with the scientists and researchers so, it keeps us abreast of what people are learning about the effect of noise and an uncomfortable sound on the brain.

Ali

And does new information pop up all the time?

Scott

It does, actually. I mean, there’s another organization we’re part of that is the Academy for Neuroscience and Architecture. And while they have focused on a lot of the impacts of the environment, you’re in, there has not been a deep focus on sound as a part of that. It’s mostly been visual because of architecture is sometimes more visual than acoustics. So, And so by participating in that conference, we’ve been in a position to help, I think influence the direction of that conversation and include noise and sound, and essentially the soundscape. That you can really weave in the idea of a soundscape into your building. So that you intentionally create a little bit of noise where you want it to reduce the amount of awareness of other activity, like in an open plan office area, or the kind of noise that might be welcomed, like fountains, or natural sounds that can sometimes help to drown out the non-natural sounds that are in the immediate environment. So, by replacing traffic noise was a little bit of a fountain, you find a more calming space.

Ali

You got into acoustics, right around your senior year of college…

Scott

You know, I actually learned about the existence as a field before I went to college. And I did not find a direct program in acoustics so I ended up studying physics and music, though I was able to take more classes in multiple places without overloading my schedule.

Ali

That’s incredible. So even in high school, you had a very good understanding of what you wanted.

Scott

So I was always into music, and I was a performer. I performed in all the musicals in my high school.

Ali

Was it vocal performance?

Scott

Vocal Performance, yeah, I was a, I am a baritone. And it was pretty good. I mean, I did alright. But I came from a small town and so I figured out pretty early on when I went off to, the district choral competitions and the other kinds of things where you see yourself against a broader range of the world, and you say, Oh, well, I’m not going to make my living as a singer, you know? So, but I was also a pretty good scientist. And so, I thought, how can I keep my involvement in music but use my skills in science. I was working as a stereo salesman at a catalog showroom. One of those places where the warehouse is upstairs, and you pick up the thing when it comes down the belt and take it with you. So, we had a listening room. And, you know, I was learning, reading about the products I was selling and learning about the acoustics of loudspeakers and, and the digital signal processing tools that were in electronics. And I thought that was the path I would be heading for, you know, either becoming a loudspeaker designer or, or electronics, music electronics designer.

Right around that time, Yale did a profile on Russell Johnson, who was the founder of Artech Consultants in New York, and Artech did the work that I do now. They worked on concert halls. And so, it was through that introduction from Yale magazine and this alumni story that I learned that this field even existed. And once I knew it existed, I felt like this is what I need to do.

Ali

Acoustics does feel like in the background, but over the years, you’ve probably developed an ear where when you’re walking through the space, you’re more attuned to the changes in acoustics. So, did you have a shift, maybe, as you slowly further got into it, where you sort of discover a new world, and like another dimension, when you’re walking through spaces?

Scott

Yeah, you can’t. I mean, it gets to a point where you can’t turn it off, if you wanted to. Part of it is that you, you know, acoustics and listening, you know, we don’t have a good memory for what we hear, just like we don’t really have a good memory for taste or smell. And the way we get around that is you develop language to describe what you experience.

There is a linguistics class I had 30 or more years ago, where they discussed the idea called the Warfield Hypothesis. And that was that you weren’t able to own an idea or a concept until you had the language to support it. And I feel like the in wine tasting and coffee, connoisseur tasting and, and in in these other areas, we come up with the language so that we can experience something, describe it in the moment, and then use that description to compare it to the next time. You don’t really remember the taste. But you remember, you’ve categorized on the signs that experience into words that you have developed a really keen sense for. So, when people say you must have a great ear, it’s not really about the quality of the apparatus on the side of my head. But it’s about the tractatus, of turning that into language, and being able to listen for something in particular, and categorize that and hold on to it to be able to compare it to the next experience.

Ali

So your understanding of a word develops over time as well.

Scott

Yeah, it does. That’s right. Yeah, absolutely.

Ali

So one thing that I was interesting to me is perfect acoustics versus good acoustics. What are some of the notable examples that you’ve experienced, personally you were inside of it, and you just realized there was something different, what made it really unique?

Scott

You know, I would say one of the times that I had that experience where I felt that I was in a very, very special place was just a very tiny stone church in Denmark. I studied in Denmark for my graduate program. I was out for a bike ride because that’s what you do in Denmark and I came upon a small stone chapel that was open and so I just wandered in. And it was one of the few times when I felt the experience of support my own sound of speaking or singing in an empty room that nobody else was there. That came from the fact that the walls were five feet thick, and it was, you know, a stone structure with plaster directly on the stone. So, it was very, very massive. And so, we make the argument in acoustic design how important it is to make heavy structures to support low frequency sound. But we’re typically arguing about, you know, extra layers of drywall, you know, so not, let’s make it two or four layers of drywall instead of one or, or let’s use real plaster, you know, which is something that is harder to get these days. But you know, an inch of plaster has a fair amount of mass compared to a normal drywall partition and so we are talking about that. But in this case, we’re talking about feet of stone and plaster. And so, the delta in in the stiffness of that surface is so much greater than anything that we might build in modern construction, that if you can fully support low frequency, in the way that a room like that does, you can really change the experience for the people who create sound, whether it’s a performer or otherwise.

Ali

So, in terms of Brockman Hall, what was the strategy?

Scott

So, the drum of the Opera House, the walls that formed the sort of horseshoe shape of the room itself, are grout filled masonry. So, it’s quite heavy.

Ali

How thick was it?

Scott

It goes from 12 inches low in the room down to 10, as you get higher. And then, you know, at eight or 10 inches thick, that’s a pretty massive, heavy wall. And then the plaster is directly applied to the inside of the masonry. So, so the walls themselves are quite massive for that purpose. We want to support the base as readily as we support the soprano. And without that kind of mass, you can favor one over the other, and that’s potentially really problematic. The bases have the hardest work to do to be heard in that way sopranos have.

Ali

It’s not. It’s not favorable.

Scott

No. So if you support the basses, then you take care of the sopranos as well so that’s good, so that works really well. And then, you know, as you move into the room, the ceiling is a bit lighter, of course, you have to support it but it’s still relatively massive. But by the time you get to the balcony face, that surface is quite small and so, it doesn’t have the ability to reflect low frequency anymore, because the wavelengths of sound are quite long, and at the lower end. So, it’s not a contender for being able to support that low frequency so it’s okay to let that get a bit lighter.

Ali

Are you an opera enthusiast?

Scott

I am, yeah, you know, part of my music education was studying voice and then learning opera arias and things. So yeah, I’ve learned a lot about it along the way. And I do enjoy. I enjoy it as an art form.

Ali

Your studies did lead you to Denmark?

Scott

Yes, they did.

Ali

Was it something specific that led you to Denmark, or was it Denmark was leading in that time for acoustics?

Scott

Yeah, they are. I mean, the Scandinavian countries in general, a lot of acoustics research comes from the laboratories there.

Ali

Is there a reason?

Scott

I believe just that it’s government supported. And they have a tradition of it. And so, it continues. Part of the undergraduate program I was in was to do a thesis, an undergraduate thesis. And so, I took my physics, education and my music education and I put it together to make a project that was a two-semester project, kind of like a capstone that you would do in architecture. And my subject was, I studied the performance halls that were on the campus at Moravian College where I was at school. And a lot of the research that I was finding to use to help inform that study came from the school in Denmark. And so, when I completed the work, submitted the project and thesis, I was looking to thank all of the people who helped me and among those that helped were some of the faculty in Denmark, whose papers I had downloaded or found. I say downloaded. They weren’t available electronically back then. I had to go to the library and get them and print them out, but anyway…

Ali

Were they in the form of books or something else?

Scott

They were typically research papers published in, in the Acoustical Society of America publication or the Journal of the Acoustical Society, or other the European Acoustical Society. Some of the papers were clearly very applicable to what I was trying to accomplish and were only available in Danish. And so, I wrote to the professors, and I said, Hey, do you happen to have an English translation? I don’t know how to speak Danish. They were very kind and supportive and they got copies of the papers to me in English. And, and so I’ve corresponded with them through the year. And as I finished the project, and was just sending out thank you notes, because that’s what I was taught to do. I wrote to the faculty there, and I thought, well, what can I say? What do I have to offer them besides my gratitude, I thought, well, I’m a student, thank you for all your help. I’d really love to study with you based on what I’ve learned from reading these papers. However, of course, I don’t speak Danish. You know, it was really just a way of complimenting them, and you know, I didn’t actually think I would go study in Denmark. And they responded to my thank you note and said, Well, we have courses in English, and we have a guest student program, and here’s how you apply, and so come on over. And so, I did. That’s how I ended up in Denmark, but it was, it was the combination of the fact that there’s a lot of research available from there. And then the connections I made in that process that led to my study.

[music]

Ali

We hope you enjoyed our episode. What stood out for me from this conversation was that in the creation of an architectural work, what is most important is to understand why something is demanded or required. If the why is accurately understood, then the parties involved can better participate in a collaborative effort that results in a design that could not have been imagined in the initial conversations.

[music]

To view the episode transcript, please visit Longitude.site. If you’re a college student interested in leading a conversation like this, visit our website Longitude.site to submit an interest form or write to us at podcast@longitude.site.

Join us next time for more unique insights on Longitude Sound Bytes.