Longitude Sound Bytes

Ep 139: Making Complex Ideas Accessible to All | LindaWelzenbach Fries (Listen)

Evalyn Navarro

Welcome to Longitude Sound Bytes, where we are bringing innovative insights from around the world directly to you.

Hi, I am Evalyn Navarro, a student from University of St Thomas and I will be your host today.

In this series, we are presenting highlights from conversations with professionals, to share examples of what they consider beautiful in their work.

For this episode, our guest is Linda Welzenbach Fries.

She is a science writer, planetary scientist, and curator of planetary materials at Rice University. Her experience in curation started at the Smithsonian Institute’s National Museum of Natural History when she was the manager of the meteorites collection. Currently, she is conducting advanced curation research with NASA and the European Space Agency.

Our episode starts with her response to what she considers “beautiful” in her work. Let’s get started.

Linda Welzenbach Fries

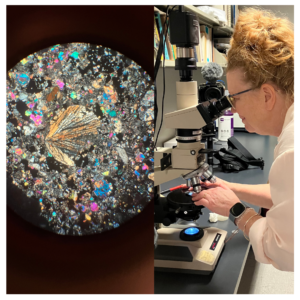

I was very much surprised, engaged and enamored the first time I looked through, and it’s not the first time I looked through a microscope, but it was the first time I had observed meteorite chondrules through a microscope.

As part of being a geologist, we work in scales, from the macro scale, observing the geology in situ, out in the field, to collecting samples and then looking at them in hand, at the hand scale, to looking at everything on a microscopic scale. I absolutely adore looking at geologic materials through the microscope.

One of the first books that I acquired when I was a graduate student were a whole bunch of these called Atlas of Rocks and their textures, and it’s basically nothing more than pictures of rocks at the microscopic scale. They were given to me by my uncle, who lovingly supported my geology habit since the age of seven. If you go to my website, you’ll see that, basically, he’s the reason I am a geologist today, and it was mostly because he gave me minerals. And minerals are beautiful. I mean, they have beautiful shapes, they have beautiful colors. You know, the thing that I find beautiful about them definitely comes from that part of my life.

Going back to the beginning here, chondrules in meteorites are unique in the sense that you can’t find anything on Earth like it. Each and every one is different. Each and every one is just really beautiful in the sense that they are colorful. They have unique shape. They have a unique structure. I think part of what makes them not only just visually engaging and beautiful, is understanding of where they come from. So, I think, as a scientist, there’s a kind of a spontaneous reaction. There’s that initial response that is completely sort of instinctive. It’s subjective. It’s the whole eye of the beholder beauty. And then as you gain more and more knowledge, you have a depth of understanding that enhances that beauty. It can become more beautiful, or become beautiful, if it wasn’t originally. I would say looking at rocks that originate from places beyond Earth and the way they are formed, to me, was beautiful on two different levels. One, because they were visually engaging, and two, because I had this knowledge of what they were and where they come from.

Evalyn

For those unfamiliar with chondrules, they are little spherical grains that make up the materials of asteroids which came to Earth as meteorites. Here is how she illustrates them.

Linda

Think of like a kaleidoscope. When you’re looking through a kaleidoscope, you see a lot of symmetry. You see a lot of color, especially the ones that are made from, like chips of glass. And then, of course, the mirrors, the number of mirrors inside of a kaleidoscope, give it a symmetry. And as you rotate the end of the kaleidoscope around, it changes. And so that’s not dissimilar from the kinds of things that we see in the microscope when it comes to planetary materials.

So, meteorites are interesting in that they were for a very, very long time, they were collectible objects because they’re odd. You know, they come from outer space. They’re interesting. When we gained the ability to do things like date rocks, analyze them in very small detail, the science for these planetary materials grew. That was around the late 1960s early 70s, especially associated with the Apollo era, when we were interested in understanding the origin of the Earth and the origin of the Moon. The Smithsonian has had a meteorite collection. Those collections came to the Smithsonian through a variety of means associated with a program that they are involved with called the US Antarctic Meteorite Program. They discovered that Antarctica was kind of a treasure trove of meteorites. And between National Institute of Polar Research in Japan and the National Science Foundation here in the US, along with NASA, they basically went and collected meteorites from Antarctica, starting in the mid to late 70s. The goal there was to better understand the breadth and the diversity of materials from our solar system through this program. Because, you know, meteorites are originally, mostly from the asteroid belt. There are some that come from beyond that, and then certainly some that come from our nearest neighbors, the Moon and Mars, that have been falling over the Earth for a very, very long period of time. Some places preserve them better than other places. Antarctica in particular, preserves them really, really well because it’s very cold and dry. Each piece basically fills in or creates a more complete or coherent picture of what the earliest part of our solar system was like. What was the composition of the solar system? What were the processes that were operating? We can’t find any of that information here on Earth. We have to look outside of that. And meteorites are essentially a very inexpensive delivery of this kind of information. And so, it’s really important for like museums and other programs to preserve as much of this material as possible, because each one is unique. Each one tells a different story, and collectively, together, we can better understand what’s going on.

Evalyn

What is the role of scientific collections in education for future generations?

Linda

I think we can use both the objects, the imagery, and what they’re telling us, obviously, in ways that can open the doors for the next generation to become explorers. I think one of the hardest things that we have to do is tread the line between being super sensationalistic about it and yet be truthful and excited about the science.

I think it’s important to also let them know this is the place to start, and that we want to hand the baton. We want to pass the baton to that next generation. I’m hoping, in the process of conveying the excitement or the beauty of what we’re doing, we’re giving them opportunities to ask new questions, to plan new ways to explore.

Evalyn

So, what does it take for a scientist to work with museums? Here is what she says.

Linda

I think the hardest areas of careers for most people who want to engage in and would love to know how to do it, or engage in it, is working in a museum. Museum is actually an amazing place, because it is the nexus of research, public engagement and essentially art. And it takes a village of scientists, designers, artists and engineers, essentially to create an exhibit that engages the public. And it’s storytelling, which is not an easy thing to do, especially when you’re trying to tell stories to a wide audience.

We’ve been able to start that process at a very small scale in our department. One of our faculties, Cin-Ty Lee, has always wanted to have an exhibit in our department as a way to also kind of balance the more artistic sort of exhibits of minerals that are over in Houston Museum of Natural History, to create a little bit more in-depth content and also make that content sort of more relevant today how geology kind of impacts our everyday life. And it was a great opportunity, because I was able to engage undergraduates and graduate students and even postdocs, and in just a couple months we developed a lot of content, and we’re able to get that printed up. And I have to say, I’ve been quite impressed with the random people that have been wandering into our ground floor area just to see the minerals and read what we have put on the walls.

Our department is evolving, and one of the things that has sort of been targeting in terms of new faculty is, is to enhance or grow our planetary science focus. And as part of that, we’ve just recently hired a meteorite scientist. I was tasked with, and super excited about actually buying a bunch of meteorites that we can use both for education and for display.

Evalyn

Curious about how to become a museum professional? Listen to how she ended up in her first role at the Smithsonian.

Linda

The reason why I became interested in museums from the get-go, and I never assumed that I would become a museum professional. My uncle gave me minerals, so I was a mineral collector, and I had access to local museums. That’s not something that everybody has and I had access to the Smithsonian because I lived in Maryland, in the Maryland, DC area. I went to school assuming that I would just become a professional geologist or maybe even go to graduate school, and I wasn’t sure what the future held, I’ll be honest, and I when I went to graduate school, I happened to be looking through the back of a magazine called Geo Times, and I saw the advertisement basically to work on a brand new exhibit at the Smithsonian, and the due date for the application was, like, two days, and there was a telephone number, and I just cold called the number, and I ended up talking to basically my future boss. And at the end of the conversation, I had basically explained, hey, you know, I’ve always collected minerals. I’ve been to the Smithsonian all my life. You know, this is part of the reason why I’m a geologist today. And I just said this would be the most amazing opportunity for me ever. This is the dream job. And then I got the job. I was just like; I can’t believe this!

Now there are programs out there. More programs for museum curation and museum science now. Every museum is a little bit different, but typically, the chief curators of most collections, regardless of the type of collection, are almost always research scientists, and they may not have any museum experience whatsoever, but they get on the job training. But I think that the profession museum studies, museum curation studies, there’s a lot more in the humanities side of thing than there is on the natural materials side of things, and I’m hoping that maybe through my job at Rice, I can help students see what is available. I can point them in the right direction. I know where a lot of these programs live, what schools provide this kind of training if they’re really interested, hopefully through a little bit of opportunities within our department, they can gain some experience. I’m at present working with Duncan Keller, who is a postdoc who came from Yale University and actually worked in some of the mineralogy exhibit development there to basically have one class, or a couple of classes devoted in exhibit development, text development, concept development, those kinds of things that you don’t normally have the opportunity to get as a student in any program, any science based program.

Evalyn

Does art influence science in the museum exhibits?

Linda

Museums are interesting in that, there is like art, there’s some degree of flexibility, except when it comes to the knowledge that they are trying to convey to the public. The way you convey that knowledge can change over time. The level of that knowledge will change over time based on the education level of the public. You have to reach some median goal. You have to account for things like accessibility and so on and so forth. But the truth of that knowledge has to be verified by experts. There are various ways to make sure that everybody agrees that the knowledge being presented is the correct knowledge. Most scientific museums try not to be anything other than objective, not subjective. Art is a little bit more subjective in my opinion. Eye of the beholder, you know, everybody is going to perceive art in a different way, and that’s okay.

In museums, we’re essentially providing context for the objects that the public is viewing. And you can tell a story about, say, you know, the evolution of humans, or, you know, here are the types of geologic environments that form these particular minerals. These are the processes that produce the kinds of gemstones that we all wear, so that people aren’t just here’s just a random object I think is beautiful, but here’s the reason why it’s beautiful. This is the reason why you like it so much. And sort of give it context to build that depth of understanding to make it even more beautiful.

Evalyn

Thank you, Linda, for sharing your experiences and insights and how you find beauty in your work. It was really interesting to learn more about meteorites and asteroids, and how there’s beauty present all around us.

[music]

Longitude

This podcast is produced by a nonprofit program that engages students and graduates in leading interviews, narrating podcast episodes, and preparing library exhibitions. To view the episode transcript, please visit our website Longitude.site Join us next time for more unique insights on Longitude Sound Bytes.