Longitude Sound Bytes

Ep 96: Teamwork in the Subsea World (Listen)

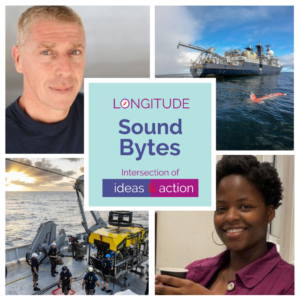

Chinenye Oguejiofor

At the intersection of ideas and action, this is Longitude Sound Bytes, where we bring innovative insights from around the world directly to you.

My name is Chinenye Oguejiofor, a Longitude fellow from Tilburg University.

Welcome to our Longitudes of Imagination series, where we are exploring the roles of individuals, technologies and research that is helping advance understanding of our oceans!

.

In today’s episode we are featuring highlights from a conversation I led with Mr. Errol Campbell, the Remotely Operated Vehicles Manager at Schmidt Ocean Institute, which is a philanthropic foundation that is enabling scientific expeditions on their research vessel at no cost to the world’s scientists. As part of the UN’s Ocean Science Decade, they are also contributing to a worldwide effort in mapping the entire seabed by 2030.

As a global law student, I was interested to hear about the amount of work it takes to map the ocean floor and what kind of tasks you would have to accomplish to fulfill that goal.

.

Errol Campbell

I have been with Schmidt Ocean Institute for just over four years now. I’m in my fifth year with them after many years in other fields as an ROV manager, ROV pilot, technician, supervisor, superintendent, offshore manager, operations manager, etc. My previous time was spent either in the military or in the oil industry. So the split was roughly about 18 years in the military, 18 years in the oil industry, and laterally, my fifth year in science and research with Schmidt Ocean Institute.

Chinenye

That’s fascinating. Regarding Schmidt Ocean Institute, would you mind explaining what Schmidt Ocean Institute is and what an ROV manager’s job is?

Errol

Schmidt Ocean Institute is a philanthropic foundation, a marine science and research institute where we enable the world’s scientists to study what they want to study throughout the world’s oceans. It was founded and funded by Eric and Wendy Schmidt, where they purchased a vessel called the RV Falkor. And latterly, we have just bought just another vessel, which is named Falkor (Too). Currently the Falkor original, as we like to call it- both vessels are in Vigo, Spain. The new vessel was an R&M, oil and gas subsea construction vessel, currently in a shipyard in Vigo to be outfitted to become a science and research vessel. And the other vessel, the Falkor, has just finished all its science, and we brought it over to Vigo to go alongside Falkor (Too) to cross deck and transition all the equipment that we are taking from the original vessel on to the new vessel. So that’s what the vessels are doing at the moment.

We solicit proposals from the world’s leading scientists and we typically get about 300 a year. We have a committee and executive committee that reduce these proposals down to around about maybe 12-ish, that we will decide to support for that coming year. That is based on quite a few different things. It is based on geographical location. Typically we pick an area that we’re going to operate for that calendar year. Obviously it makes sense if, for example, the last couple of years we’ve been circumnavigating Australia, so the bulk of our scientists came from the Southeast Asia and Australia area. And the focuses we had identified for the last couple of years were the plastics, tsunami hazards, coral reefs, coral preservation, etc. So again, depending on the geographical location and the preferred field of study for that period will determine on what scientists we support. Once we decide who we’re going to support we will typically allocate them vessel time. So just for ease, say we pick 12 different science groups, then we would allocate a time slot for each group of scientists.

Chinenye

To study it?

Errol

Once a year. One will join in January and conduct science typically for a month. And then we’ll take them back in and bring on the next group and take them out. We also have provided whatever platforms they need to conduct their science on our vessel. And depending on what they’re studying, if they need the ROV, if they want the ROV, if they want all our science sensors, if they want to do mapping, if they want to take whatever kind of samples, we plan ahead of time, and we prepare accordingly to accommodate the relevant science group. We have two ROV’s. We have our ROV Subastian, which is a big work class ROV, typically the size of a big SUV, has robotic arms and sensors, the ability to take samples, whatever the samples may be. They may be rock samples, sediment samples, it could be gas, water, whatever samples, and obviously, we film everything as well in 4k video, and live stream most of our dives on YouTube.

Chinenye

Yes, I watched them! Some of your YouTube videos. It was very fascinating.

Errol

Yeah, it is really good. And that’s one of our goals, is to attract a larger audience and pass on our knowledge. And that is the key driver of the big deliverable from the science community, is that everything we do find has to be shared and accessible, so that’s one of the caveats to our supporting scientists. Okay, we will take you to where really want to go, we’ll enable you to do what you want to do, but you’ve got to share what you find.

Chinenye

I recently read an article that said that within the US specifically, since that is where SOI is based, people assume because scientists who study ocean mapping are doing this based off of taxpayers’ money, that all the information has to be shared. Would you say that this is the situation all around the world? Because, as far as I’m aware, as of 2017, that’s when ocean mapping became more of a phenomenon worldwide- would you say that it’s the case that around the world, they do tend to share the data that they get when mapping the ocean floors?

Errol

Yes, I would say. Obviously there’s been certain types of mapping or whoever done for self-interest in the commercial world. But I think the push for Seabed 2030 is bringing everyone together to share the data. So I can’t say for certain who pays for the data acquisition, but I think the trend now and the objective of this is for everyone to share their data.

Chinenye

Honestly I find it very interesting.

Errol

There’s many reasons you map the ocean floor, you know. So obviously, it’s great to map it to know what we’ve got and it gives us a knowledge of what’s where, and helps our studies or the world’s ocean, whether that be for whatever reason you’re studying it. The most exciting thing from an ROV perspective is we can identify areas of interest, because there’s so many areas, depends on your perspective on it, right? It makes us so much more efficient from a scientific perspective. If the area has been marked, for example, when it identifies hydrothermal vents or whatever, wheel falls or whatever it identifies, we can target dive with our ROVs much more efficiently, we can go straight to where we want to dive and dive, it means the ROV is not looking for something to dive on, you’re not wasting days and days of ROV time, vessel time, trying to find what you want to study. You know if the seabed has been marked for example, then you know exactly where you want to go.

Chinenye

So you enjoy having that certainty of knowing where your ROV is going?

Errol

Yeah, it just makes everything so much more efficient because you’ve taken a team of scientists offshore. The last thing you want to do is waste days and days looking for something you really want to be getting samples 24/7 if possible.

Chinenye

Understandable.

Errol

I would say the biggest highlight for me would be identifying targets of interest.

Chinenye

Speaking of your ROV management, as a Remotely Operated Vehicle manager, what would you say is the hardest part of your job?

Errol

People probably. There are several things. We’re quite fortunate in this situation with SOI, because I’ve got a very long experienced background and a lot of contacts in the ROV industry globally. I’m from Scotland. I’ve lived in America, lived in Singapore, have operated globally for many years. So I have a really good network. So that helps, but keeping good people in the pandemic impact has been a big challenge for us. Our ROV Subastian goes to four and a half thousand meters deep. So if you’re putting a high voltage and electronics and hydraulics and everything, four and a half thousand meters below the ocean, it’s always challenging. So it varies, really. Making sure you’ve got good, competent people, and then dealing with all the technical challenges, dealing with scientific challenges. There’s nothing really bad, but there’s lots of different challenges. There’s nothing that I dread and nothing that we can’t overcome. But, you know, there’s different challenges, different times, sometimes weather is a challenge, anything.

Chinenye

Well, as they say, teamwork makes the dream work. And you surely put that to practice.

Errol

Yeah, absolutely. If you listen to all our scientists, we do end the trip with briefs from all our science groups. And when you hear them, that’s one of the biggest things they say about SOI and the Falkor original, how good it was, and how accommodating it was, and how much of a team spirit there is. Everybody helps. If something breaks, every department will help to fix it, whether that’s the ROV technicians, whether we have to involve the engineers or the marine technicians. And so you’re right about the teamwork.

Chinenye

I really appreciate it. Because as technology keeps evolving, and as we’re moving on centuries, it seems that people keep relying more on machinery as compared to human beings. We can fix said machinery in the event that something goes wrong, so it is nice to see an initiative that focuses more on the core teamwork that helps make the machines run in the first place. Now in regards to how creative you can be on the job, I understand with being an ROV manager and working with the different types of scientists that you have, and the proposals that they bring in at the same time, is there any room for creativity in your research process? Or in your collection process as well?

Errol

Yeah. Always. But for most of the science we do, it can be repetitive. Some you’ve done before, whether it be using gas tights, or majors, or niskin bottles for water samplers, or rock boxes, core samplers, whatever. It can be repetitive, you know what I mean. But we’re always making things for the scientists and the scientists are always bringing new pieces to integrate onto our ROV, and there’s always room to make things better. And it’s just an ever-evolving process. If you bring something to put on the ROV tomorrow, and my team can look at that and say, it would be better if we did this, or if we did that, or whatever, then we’re always working together to enable the scientists to do what they need to do, and do it more efficiently.

Chinenye

So there’s always some sort of room for creativity with the different minds that come together to make this project a success.

Errol

Absolutely.

Chinenye

That’s always nice to hear.

Errol

Yeah. Again, typically, you’re well-prepared ahead of time. Because when we do this process of cruise planning, then we know. We have cruise calls, like six months out, three months out, a month out, so we’re really addressing all your questions in the months preceding up to your cruise, with a goal of being totally prepared. Although it does happen on the job, and always will, we try to be as best prepared as possible. Sometimes we’ll test things before the cruise. We’ve got engineers that take the drawings of whatever we’re trying to integrate, and we’ll have planned integration on to the ROV ahead of time so we’re not trying to figure it out and waste your time when you arrive.

Chinenye

With that in mind, what would you say exactly is, or if there is, a sort of formula to get the results that you intend to get? As you said, you have routine checks six months before the cruise, six months before the research itself is done. But for there to be room for creativity and imagination in garnering of your results, is there any formula to it, do you say? One person checks whether the ROV’s are working, another person checks where the other scientists are lined up, etc., and they assess whether the scientists have any creative ideas? Is there some sort of formula for it?

Errol

There is a process. A formula? I’m not so sure.

Chinenye

But a process instead of a formula.

Errol

The processes and procedures we have in place for everything, everybody’s working on it. We look at a science proposal, and then once we’ve got all that information, then many teams are working on it. The outreach media teams now are all working on how we’re going to live stream these. The ROV team are looped in and planning on integration sensors or whatever. The MTs, marine department, are looking at what their deliverables are from a mapping perspective, or a sample perspective, right up to the chief officer and the captain of the vessel. They’re involved in it, they know where they need to go, what they need to do. Are we transiting from A to B? Are we mapping this? You know what I mean?

Chinenye

Yes.

Errol

It’s a collective effort for sure, right from the Executive Director down to the people on the vessel. Everybody is involved, whether it’s- their chefs know that they need to cook for X amount of people. Everybody’s involved.

Chinenye

I think it’s very innovative. With innovation in mind, what would you foresee the future being for those who plan to map ocean floors? Are those within your field of work, whether it be for Schmidt Ocean Institution or any other group that seeks to map the ocean floor? Perhaps so as to reach the 2030 goal specifically.

Errol

Yeah, that’s a good question. And I think everybody who can needs to get involved in it. If you’re mapping from one vessel, you’re only mapping where you’re going, right? You can’t do anything else, you’re mapping where you’re going. There are other options. Whether you work in ASVs, and AUVs, and things like that, it could be expanding your footprint. They could be sent out on autonomous machines to mark X areas or wherever, and then rejoin you for the run. So maximizing potential I think has to be the way forward for everybody. Obviously it’s different for different organizations, but I think from our organization we will expand our remote footprint over the coming years and enhance our ability to map the seabed by more assets, such as ASV’s AUVs, and things like that.

Chinenye

It is my understanding that mapping the ocean for us is a very expensive endeavor to take on for any institution. It does seem like that would be a lot of work for anyone in the future, no matter what it is.

Errol

Yeah. But it’s like everything. Communication and collaboration is going to make it better. I think the commercial world needs to get more involved as well. For example, we have millions of vessels going all over the world every minute, every day. The more we can get involved, the more we can get mapping, the quicker we can attain our goal to map the seabed by 2030. Again, there’s areas that are more accessible than others, like, for example, can we involve the commercial industry? Everyone in all these shipping groups, whatever kind of vessels, can we get their buy-in to this? How do we get their buy-in? Because obviously, they are commercially driven and they want to get from A to B as quickly as possible, from a commercial perspective, so I don’t have the answers on how we can fully engage the commercial world. And then the other challenge is the more remote areas that- people don’t typically go and map these areas, right, there’s a huge cost involved, time, you got to have the assets to do it. So I think all of the like-minded institutions need to collaborate openly. For example, there’s no point in you going to the same place as me. So if we talk and I say, I’m going here, and you can say, Okay, well I’ll go there, you know, and-

Chinenye

Makes the work faster. Division of labor.

Errol

Yeah.

Chinenye

With your 18 plus years of experience, was there any set person, or were there a set of people, that helped you get to where you are today, with your background? Having gone to college and to where you are now, were there people that guided you along the path that you took?

Errol

Yeah, definitely. That’s like any work, any focus in life, any area of study. You’re always going to be working with people and learning from them. What we called back in the day, it was like journeyman, or tradesman, or whoever will take care of you for a certain period of time during your mentoring procession, and then you move on and you actually progress and become one of these mentors for the more junior people. So yeah, that happens everywhere, happens in the military, happens in the oil industry, it happens in science and research. That’s the case. You go in, you’re employed for this at the level and the skill sets that you have, and then you progress.

Chinenye

Slowly but surely, yes.

.

Chinenye

It is amazing to know that there are people out there who take it upon themselves to map the great ocean floor. One crucial thing that stuck with me from talking to Mr. Campbell is that there is always room for change. And if not, it just means you are happy with your finished product. Specifically when it comes to mapping the ocean floor, you know that there is so much that needs to be done, so much that needs to be accomplished, and at the end of the day sometimes your best really is all that you can do, which was really eye opening to hear, especially with the task as big as mapping the ocean floor. I hope that whoever hears this, and whoever gets to hear this interview, has an eye-opening experience just as I did and remembers that teamwork makes the dream work, and that working together can bring us much further than we ever thought we could.

.

We hope you enjoyed today’s segment. Please feel free to share your thoughts over social media and visit Longitude.site for the episode transcript. Join us next time for more unique insights on Longitude Sound Bytes.